The National Flood Insurance Program has introduced new rules that mean the days of heavily subsidized flood insurance are over. If you want to live close to the water, you’re going to have to pay up.

The National Flood Insurance Program’s new method of calculating flood insurance rates is called Risk Rating 2.0, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, who runs the program, says the new rates are more equitable and indicative of each home’s actual flood risk.

“The NFIP’s new rating methodology is long overdue since it hasn’t been updated in more than 40 years,” FEMA said in a statement.

The new rating guidelines, which went into effect Oct. 1 for new customers and will take effect for current customers when their policy renews on or after April 1, will increase the cost of flood insurance on roughly 77% of existing NFIP policies, according to NFIP data. Of those, most will see a minimal change — the average premium increase is $8 per month, or $96 per year. But some residents of coastal states like Florida and Texas will see their rates skyrocket by thousands of dollars in year one alone.

Here’s what led to the drastic changes:

NFIP debt problems could no longer be ignored

The National Flood Insurance Program was established by Congress in 1968 to provide flood insurance to flood-prone communities. Flood damage isn’t covered by homeowners insurance and, at the time, the private insurance sector didn’t have a good way of predicting or underwriting flood risk.

Part of the problem is the NFIP didn’t either, says Michael Poulton, CEO of Poulton Associates, a company which provides private flood insurance and other types of catastrophe insurance. “The way they calibrated their system, everybody paid the wrong rate, nobody paid the right rate with the NFIP,” Poulton says.

Anyone with a federally-backed mortgage is required to buy flood insurance if their home is within a high-risk flood zone. As the country’s primary source of flood insurance, the NFIP has been insuring these high-risk properties — often at heavily subsidized rates. Since the program is funded by the flood insurance premiums it brings in, it often has to borrow money from the federal treasury to pay out claims. Poulton says that this has led to a program that is over $20 billion in debt.

“The original idea of the program was that we wouldn’t keep funding natural disasters — people who lived in flood-prone areas would buy insurance and we would stop paying for it,” says Poulton. But “every few years [the NFIP] drives up this big debt and then somebody in Congress says we’ve got to relieve them of the debt,” he says, referencing the roughly $50 million that has already been forgiven by Congress.

Poulton says one way for the program to become solvent is to correlate risk with rate, and the only way to do that was to increase the price of flood insurance for those properties with the highest risk.

What changed?

For decades, flood insurance rates were mostly based on where your home was located on outdated FEMA flood maps, says Michael Lopes, communications director at First Street Foundation, a nonprofit that researches flood risk.

“Up until [the rate change], you could live right across the street from a high-risk flood zone and only have to pay $480 [for flood insurance], and the person across from you might have to pay thousands,” Lopes says. The zones were generally tied to fluvial (river flooding) or coastal flooding along major bodies of water and nothing else, he says.

First Street Foundation’s own flood risk tool, Flood Factor, includes several variables in its flood risk models, including sea level rise, storm surge, fluvial flooding from smaller bodies of water, and pluvial flooding (measures the impact of rain where it falls), all of which paint a much fuller picture of flood risk.

No one except the NFIP knows exactly how flood risk is being calculated under Risk Rating 2.0, though it’s likely it incorporates some of the same variables that Flood Factor uses.

Are the changes enough?

Members of Congress from both parties voiced their opposition to the rate hikes, calling for delays to the new plan. Some fear the rate increases could lead to households forfeiting their flood insurance altogether and relying on disaster aid from an already indebted FEMA. Others feel the increases place an unfair burden on working class families. But Lopes says that, based on risk assessments, the rate changes appear to be more fair.

“What we had under the old system was people subsidizing other peoples’ flood risk,” Lopes says.

By undercharging for flood insurance, the NFIP was subsidizing property development in floodplains, and subsidizing risk for the residents who had long benefited from the program’s below-market rates. What’s resulted is a program that has mostly helped wealthier coastal residents at the expense of lower-income residents further inland.

FEMA has branded its pricing overhaul as “Equity in Action” and promised rates that are “equitable, easier to understand, and better reflect an individual property’s flood risk.”

However, Poulton isn’t convinced the new plan goes far enough. He sees two shortcomings in the NFIP’s new plan: a $12,125 annual cap on flood insurance rates, and the continued availability of policy discounts that are unrelated to a home’s flood risk. “You can build as close to the water as you’d like, and the most you’ll ever pay for flood insurance is [$12,125 a year],” he says.

Poulton fears the new rates and annual rate cap won’t be enough to discourage property development in coastal areas most at risk of climate change.

“[Coastal development] destroys habitat, it puts a big structure in a place where it’s never going to stay,” he says. “At some point you need to say ‘risk equals rate’.”

How to deal with a premium increase

If you’re one of the roughly three-quarters of policyholders who will see their flood insurance go up under the new rating system, you have some breathing room — your rate increase won't kick in until next spring.

The amount you pay for flood insurance is based on your home’s risk of flooding. If you're buying a new home, be sure to find out if it's located in a flood zone. By taking steps to lessen that risk, you can better protect against flood damage and pay less for flood insurance. If your premiums are going up under Risk Rating 2.0, here are some things you can do to mitigate your home’s flood risk and lower your rates:

Floodproof your home: Elevating your house, moving water heaters and other systems to higher ground, filling in your basement or crawlspace, and installing flood openings on exterior walls all decrease your home’s flood risk and can lead to lower premiums. Check out FEMA’s guide to flood retrofitting for more information.

Raise your policy deductible: Raising your flood insurance deductible to the $10,000 max can reduce your rates by as much as 40%, according to FEMA. But a higher deductible means you’ll need to pay more out of pocket if your home is damaged in a flood. Before increasing your deductible, make sure it’s set to an amount you can afford.

Use an elevation certificate: An elevation certificate is documentation of your home’s flood risk. If you have an EC, provide it to your agent — it could help lower your rates.

Community-wide discounts: Policyholders in communities enrolled in the NFIP’s Community Rating System are eligible for discounts of 5% to 45%, according to the NFIP. Check here to see if your community participates.

Poulton says many who are overcharged for NFIP coverage turn to private flood insurance that is written and backed by private companies. “Those who are overcharged are the ones who go to private flood, those who are undercharged usually stay with the NFIP,” Poulton said.

Data isn't available based on the new rates, but a 2017 study by Milliman found that 77% of single-family homes in Florida, 69% in Louisiana, and 92% in Texas could all see cheaper premiums with private flood insurance.

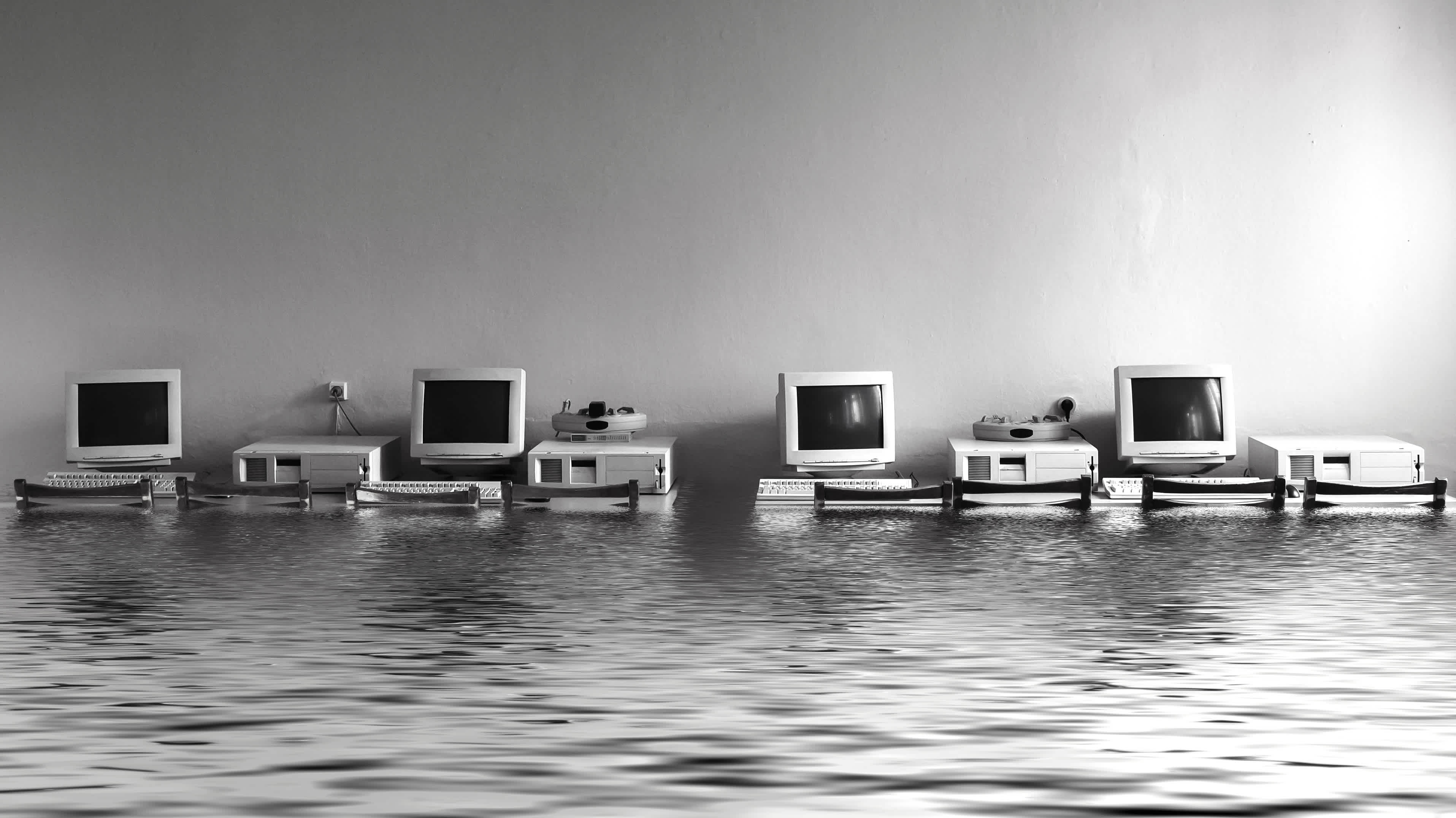

Image: Rolaks / Getty Images